Sitting back this week to listen, to amplify Black voices, and to become better educated about systemic racism and institutions of policing, I found myself once again confronting and taking a hard look at the way racism and legacies of oppression have shaped the art world and, in particular, art history. And here, I am not talking about the kind of revisionist art history that has attempted to rescue and include both People of Colour and women into the canon of art history— a project that has had its own peculiar set of politics, agendas, and criticisms that could fill multiple blog posts. Instead, I am thinking more about the way art historians have traditionally and systematically avoided dealing with the significant role and influence that protest art, street and graffiti art, and mural and poster art have played in the art world and beyond. There is still a powerful elitism present within the academy and among art critics that refuses to acknowledge how this form of visual culture can and should be considered art with a capital A.

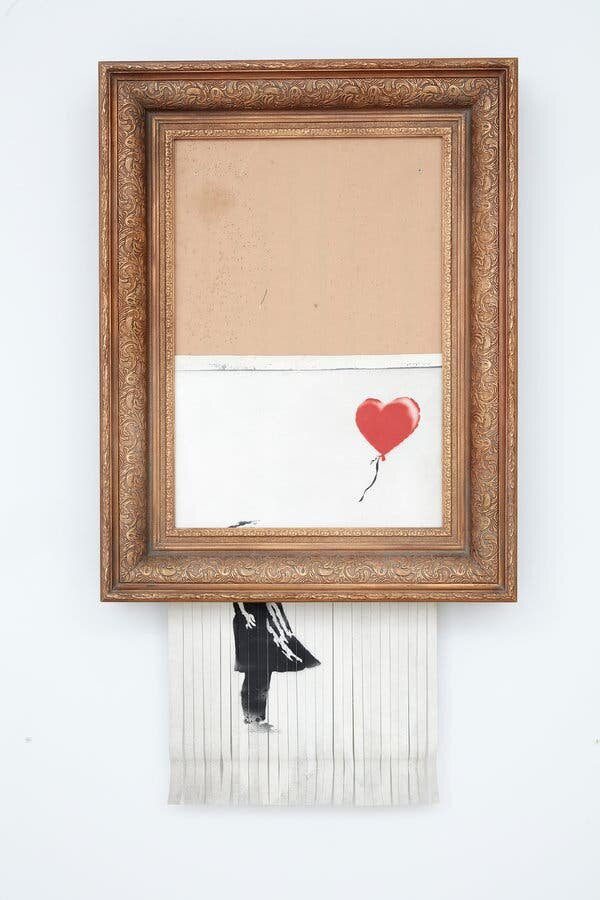

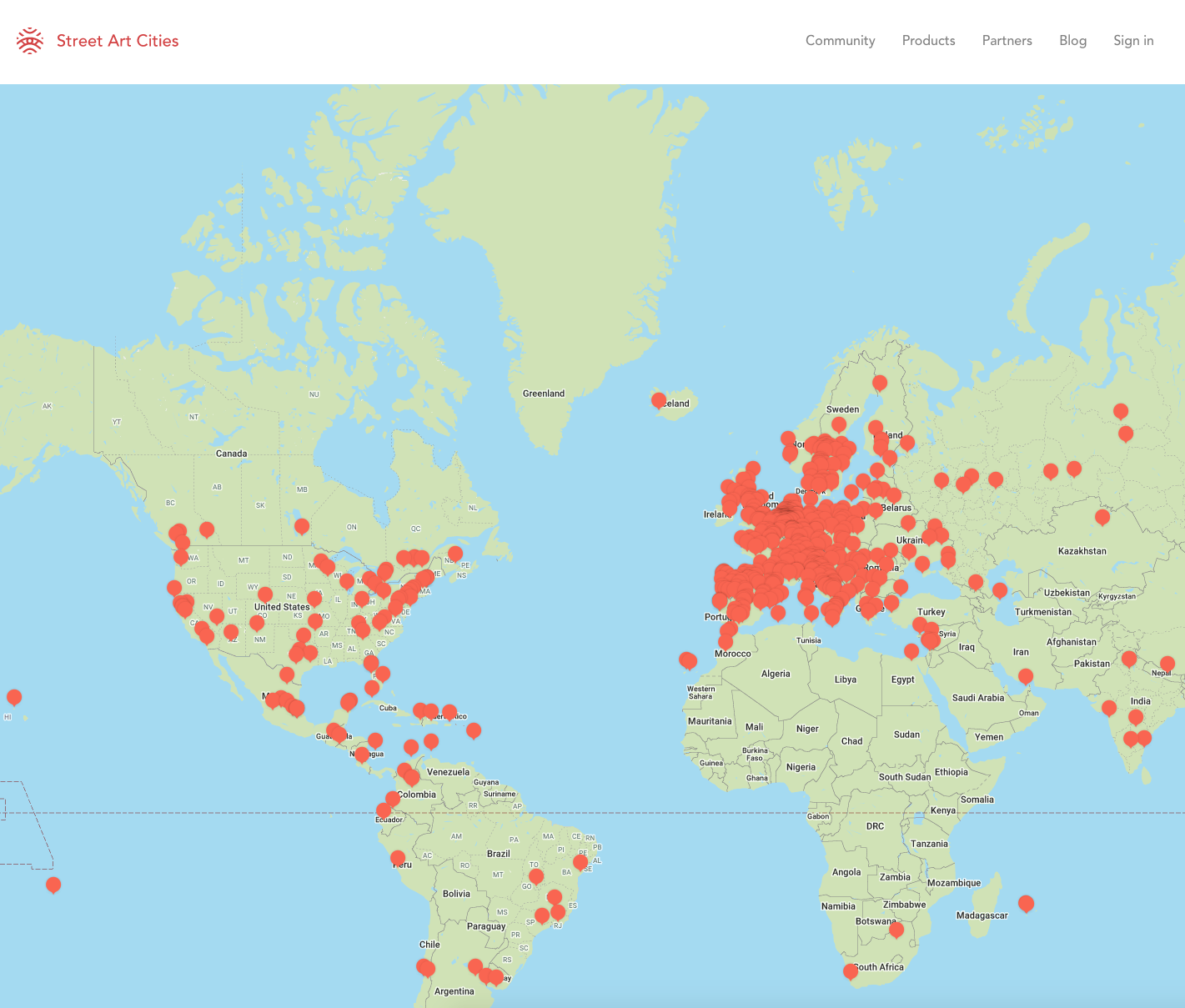

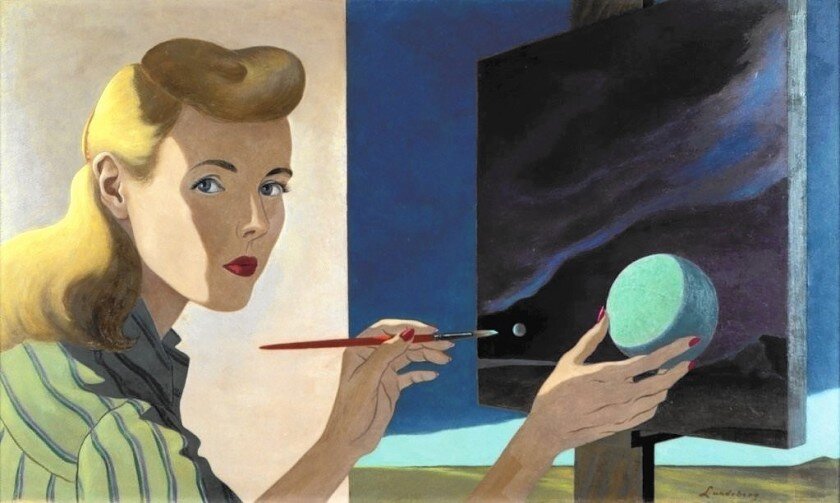

I was once again reminded of this inherent bias a few days ago while participating in an online e-mail thread among art historians about the instantly iconic Black Lives Matter street mural that was commissioned by the Washington D.C. mayor and debuted a day after #BlackoutTuesday (see image below). The discussion, while lauding the importance of the visual gesture and its impact, quickly turned to comments and questions about whether the mural was a work of art. Some claimed it was too “performative,” “graffiti-inspired,” or “political” to operate as a work of art, while others called it a work of protest or without artistic intent, failing to acknowledge the reality that artists were hired to complete the piece. Not unlike those art historians or art critics who refuse to take contemporary street artists seriously (and especially the ones with instant popular recognition and global influence and acclaim such as Banksy, KAWS, and Shepard Fairey— white artists who cite New York graffiti culture and African American writers and artists as their primary influence), there is a long practice within art history to dismiss the popular, the untidy, the difficult to categorize, and the unruly. Despite the legacy of the avant-garde and its impact on modern and contemporary art history— which it must be pointed out is disproportionately made up and shaped by white male artists, practitioners, and theorists of the 20th century— there exist critical omissions that cannot reconcile the high/low art divide that has plagued the art world since the days of Clement Greenberg and his critiques of Andy Warhol and Pop Art. Posters, graffiti, mark-making in the streets, and a myriad of other forms of difficult to place urban art-making and performance exist in this space, and it is not surprising that many of the practitioners associated with these works, and their critical histories, are People of Colour.

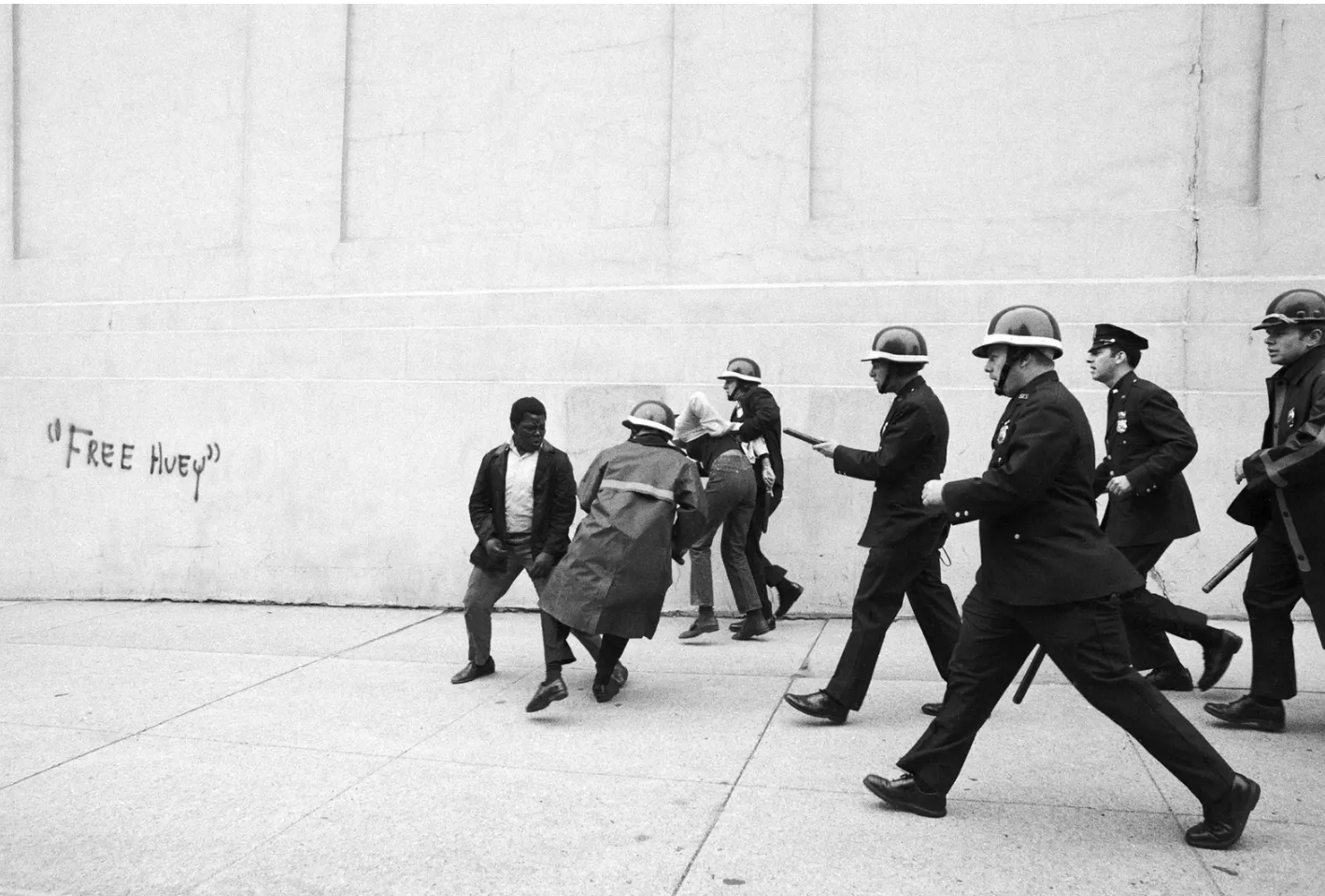

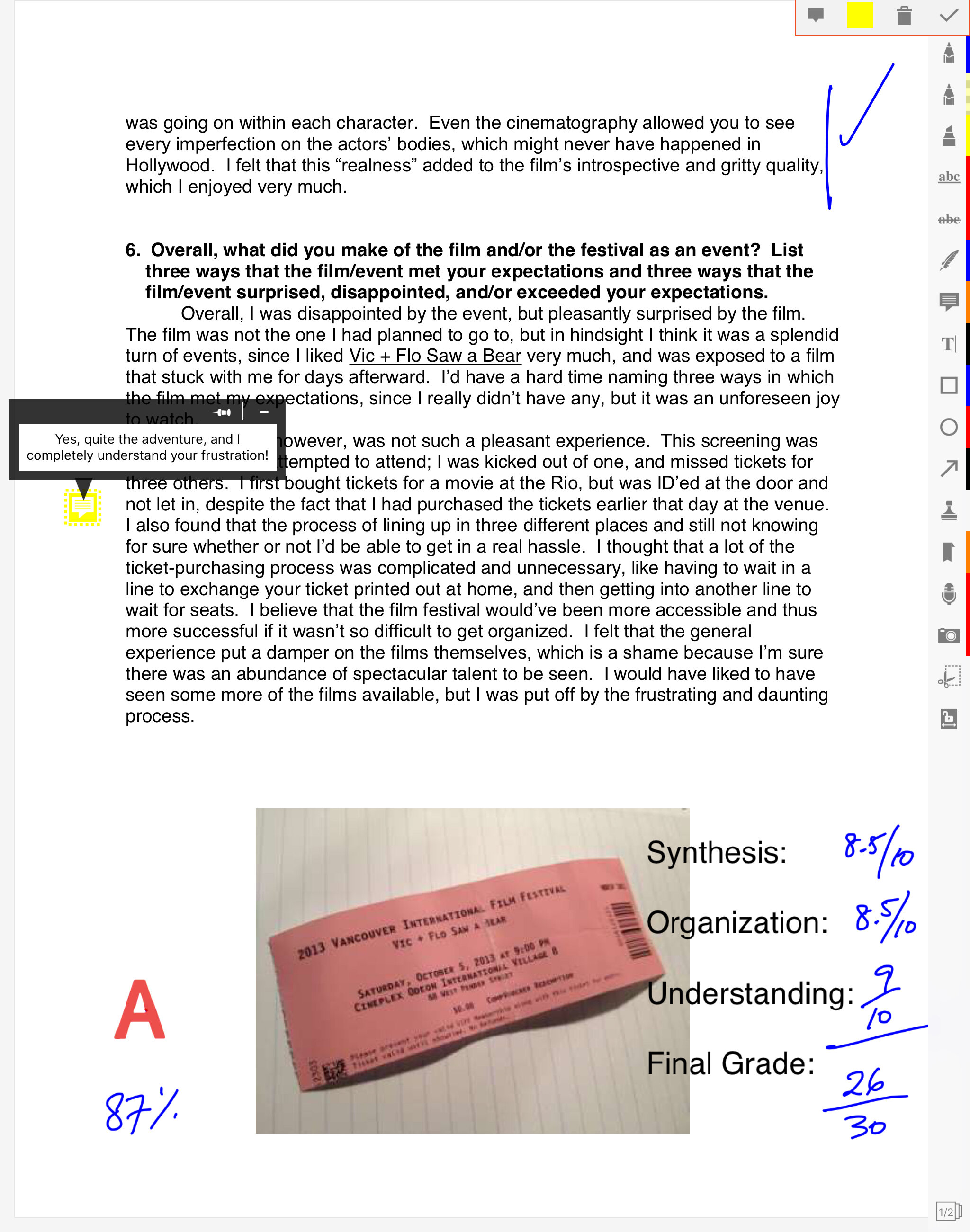

Pictured above is an image of NYC police officers confronting protesters in 1969 with the “Free Huey” graffiti marking on the left signaling reference to the jailed Black Panthers political activist and co-founder Huey P. Newton, and below an image of the Black Lives Matter street mural commissioned by Washington D.C. mayor Muriel Bowser.

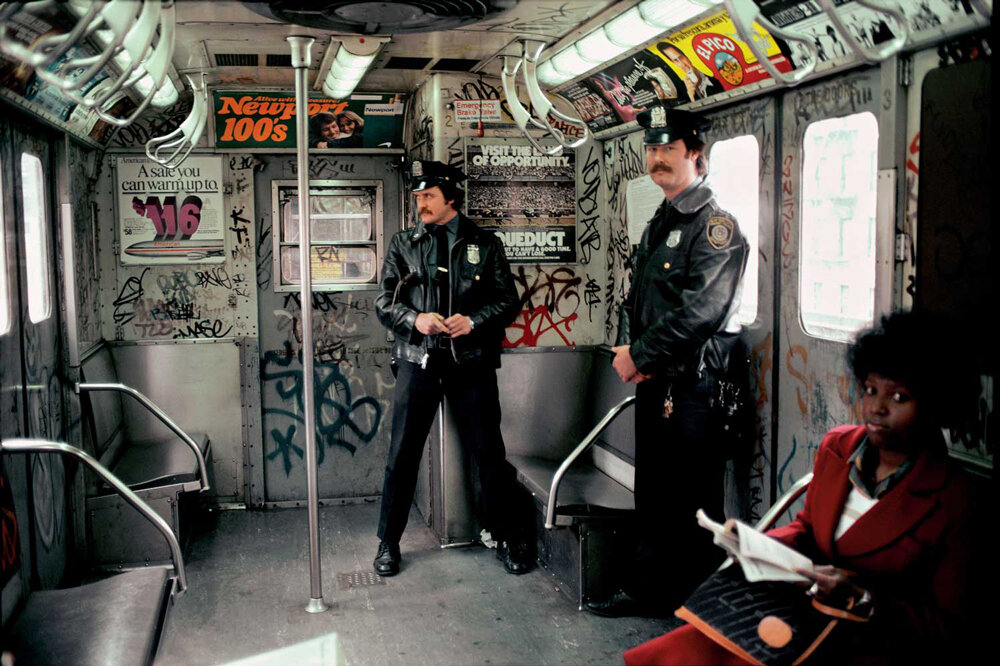

In lieu of my weekly round-up, I invite you to read Ivor Miller’s “Guerilla artists of New York City,” an essay I routinely assign to students in both my “Intro to Visual Art, Urban, and Screen Culture” and “Urban Graffiti and Street Art” courses. Published in Race and Class in 1993, the powerful and now classic essay tracks the early history of graffiti art in New York City, and gives voice to the young artist “writers” who participated in the movement. Importantly, Miller, who is not an art historian, correctly understands and analyzes the practice of graffiti as a form of art. As Miller writes, “Protest and self-affirmation are inherent in both the music and visual art of this inner-city renaissance. Grand Master Flash and the Furious Five came out with ’The Message’, ’Survival’ and ’New York, New York’. Melle Mel rapped the apocalyptic ’World War III’, with lines like ’War is a game of business’, and ’Nobody hears what the people say’. Writers painted names like ’Cries of the Ghetto’, ’Slave’ and ’Spartacus’, and eventually dominated the subway system with whole car paintings depicting the violence of their lives: images of guns, gangsters, and political statements like ’Hang Nixon!’ abounded. Subconscious though it may sometimes have been, the large-scale, collective motivations of writing culture reflected some of the important issues of the day.” Perhaps this essay will help spark more conversations about what is desperately missing from a more inclusive art history and art world, recognizing and listening more carefully and critically to Black voices and experiences.