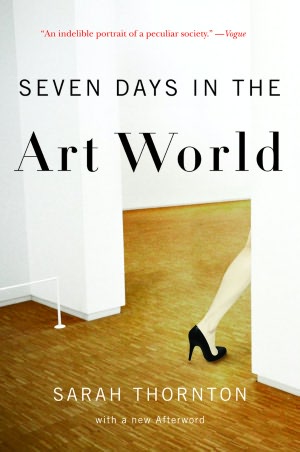

Sarah Thornton's book was one of the books that was assigned for reading in the pre-departure classes. Her final chapter on the Venice Biennale is eye-opening and highly recommended.

To understand the Venice Biennale, it is important to consider both its very long and often politically animated history, but also the way the event has become spatially charged, creating literal insiders and outsiders to the main venues in Venice. The Biennale has also been subject in recent years to increasing scrutiny for the exhibition’s influence on the world’s very hot contemporary art market. These were themes that we explored in the pre-departure field school classes as part of the larger understanding of the connections between New York—as the center of the art world—and the role of art fairs, biennales, and global exhibitions in determining how audiences come to “value” art. (Two resources that were especially helpful for students to begin this exploration and I recommend here are: 1) the final chapter on the Venice Biennale in Sarah Thornton’s Seven Days in the Art World; and 2) the Vice produced documentary on the Venice Biennale from 2013, pasted below).

For the 2015 Venice Biennale, the appointment of Okwui Enwezor as curator signaled an important and potentially critical turn for the 120-year old institution. Enwezor, a figure known in the art world as both an ardent critic of the art market and an art theorist steeped in research concerning global modernism and formations of postcolonial modernity, proved to be a bold choice for an event that many have criticized in recent years for being overly commercial and launching global art trends that eventually trickle down to the auction houses. At the core of Enwezor’s curatorial vision for the 2015 event was the desire to interrogate both the pleasure of viewing and fetishization of the object so key to many individual’s understanding, appreciation, and valuation of art. His theme, “All the World’s Futures” is devoted in Enwezor’s own words to “a fresh appraisal of the relationship of art and artists to the current state of things.” One part of this appraisal is tackling head on the often taboo relationship between art and money. To this end, the central and featured art performance at the Biennale this year is Capital: A Live Reading which entails a daily live reading of the complete four volumes of Karl Marx’s Das Kapital. Of the project, Enwezor says in an interview with The Guardian: “I wanted to do something that has contemporary relevance and speaks to the situation we are in. And so I thought of Das Kapital, a book that nobody has read and yet everyone hates or quotes from.”

The compact catalogue for the 2015 Venice Biennale with this year's theme "All the World's Futures" logo on the cover.

Now for those who recall Enwezor’s position as the first non-European art director of the equally prestigious Documenta 11 art exhibition a decade and a half earlier (from 1998-2002), the curatorial vision of the 2015 Venice Biennale follows closely in both approach and execution—an ideas-driven, decentered exhibition, interested in opening up conversations about “shadow histories” that redress past exclusions from the most important art event in the world. To be sure, many critics have been struck by how entire pavilions in the 2015 Biennale are empty of “art objects” and have been made into environments or overtaken by elaborate installations and platforms for performance—art forms that traditionally resist easy commodification and consumption. For some critics, this is refreshing and potentially transgressive—see for example the review by New York Times art critic Roberta Smith, while for others it is a “joyless” failure—see for example the review by artnet’s Benjamin Genoccchio .

When visiting the Biennale, this curatorial vision was immediately apparent in the minimal, stripped down, and emptied pavilions. I found the experience to be incredibly powerful and thought that the spaces were somehow less burdened and more focused in both vision and message without all the accumulation of things. Having in past visits to the Biennale been overwhelmed with both the information and number of art objects placed in each space, this approach was incredibly radical. This was especially the case at the Giardini venue where nearly every national pavilion presented viewers with open space, sensory immersion, and interactivity. This served to activate art as an "in process” experience versus art as an experience of passive consumption.

Some highlights (assembled in the photo gallery of pictures I took at the Biennale) include Japan’s Chiharu Shiota’s The Key in the Hand, which uses the lost key as a launching off point to explore public and private memory; Korea’s artist dup Moon Kyungwon and Jeon Joonho’s digital installation to explore new and supernatural visions of the artist’s future role in society; Germany’s Fabrik and their creation of a kind of gaming platform that audiences get to passively (but with full awareness) consume as “activists” in both a statement and critique of today’s political landscape; Hungary’s Sustainable Identities installation by Szilard Cseke which invites audiences to explore multiple and dislocated identities; the USA’s rich Joan Jonas retrospective that has audiences come face to face with the fragility of nature; and Switzerland’s unique and full sensory Our Product, a project that artist Pamela Rosenkranz created to approximate the skin colour and smell of the average European to transform the pavilion into a living body. Other notable pavilions operating in this vein include the Austria, Serbia, Israel, France and Norway exhibitions. One after the other, these places engaged audiences with radically new and different spatial propositions. All in all, a successful approach in my estimation. And while many will likely still ask "where is the art" when visiting this year's Biennale, others will walk away broadening their definition of what art can consist of while expanding the possibilities for the artist's role in contemporary society.

Inside the Serbian pavilion, the installation United Dead Nations by Ivan Grubanov explores the idea of "nation" by looking at the flags and banners of nations that no longer exist such as Yugoslavia, Czechoslovakia, and the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The colours all appear to merge and suggest an unexpected kind of unity.