Tell us a little bit about yourself—your background, major program of study, reasons for taking this trip, and anything else interesting you want to share (maybe something people might not know about you).

I am an incoming Master of Arts student in Art History at the University of British Columbia with an undergraduate degree in anatomy and cell biology. I decided to pursue art history after four years of life sciences and laboratory research after having discovered it through elective courses. I liked how art history offered a different way of relating to the world, how it was able to derive information beyond relying on data points and thereby, exercise a greater range of human faculties. While I understand the limitation and crudeness of science, I will always uphold it for doing the grunt work it takes to unlock information about the natural world inaccessible by other means.. My MA research interest therefore seeks to reconcile science and art by expanding art historical discourse through the inclusion of scientific knowledge. Through this Field School I hope to be inspired, to find an instigation where science merges with art to productively contribute to a discourse. So far, I have been blown away by the Palaise de Tokyo’s exhibition Le Reve des Formes where there was a strong interest in confluencing art and science. I am also inspired by the many residency opportunities in Paris where “residency” is actually called a “laboratory!” I have similarly walked by galleries called “Writing Laboratory,” “Le Laboratory,” and “Drawing Laboratory.” I LOVE THIS TERMINOLOGY. To acknowledge that art has always been experimental, that it is an endeavor of chance meaning-making is a mentality of refreshing honesty.

Alice (center) and field school students pose in front of Manet's iconic Olympia (1863) at the Orsay Museum.

Alice in silhouette looking out onto to the Seine river towards the Louvre from the behind the famous Orsay clock.

What has met or exceeded your expectations or surprised you about Paris so far?

I was surprised by the degree of conviviality between French Canadians and local Parisians. I grew up in Quebec so I speak with a strong hint of French-Canadian accent. I also completed my undergrad at McGill University, further galvanizing my dialect. Whereas the Parisian French is a more modernized, evolved language, the Quebecois French is a rural, old version of the language from colonial time. From a young age, I had always found the Quebecois accent to be embarrassingly provincial. Coming to Paris therefore I was very self-conscious about how I spoke. Half of my energy went into suppressing the accent and feigning to be a local. While my Anglophone colleagues might find it advantageous that I speak at least a variation of French, I curse the grass on the other side because sometimes I wish I knew no French at all rather than a red-neck version. To much of my dismay, the locals saw right through my disguise. The first thing that the Sennelier shopkeeper said to me was: “Vous êtes Quebeçoise!” At the L’Orangerie, the security guard asked me if I was Canadian when I spoke to him. From these encounters, I find myself increasingly interested in elucidating what the French thought of Quebeckers; perhaps my insecurities were unwarranted. On one afternoon at the Tuileries garden, a francophone friend and I talked for almost two hours with a local Parisian about the history of France and Canada, about the French’s general perception of Quebeckers (“They are our cousins…our Americanized cousins.”) Ah, if only there was more exchange between France and Quebec! If only the motherland realize how much her enfant terrible prides itself on its French roots—its valorization of art and culture, its good food and way of life—she would have been proud.

At the Palaise de Tokyo I met a tour guide who exuded an unyielding, uncompromising Quebecois accent. The ease and pride with which he spoke was, in the strangest way, empowering for someone who is trying to strike a balance between assimilation and individuality. After two weeks in Paris, I have come to accept that childhood accents are unforgivingly permanent. They will thwart any attempt of forgery, forcing me to appreciate things that I cannot change. During a time where nationality bears heavy connotation, being evidently a French-Canadian, turns out, is a responsibility I need to uphold.

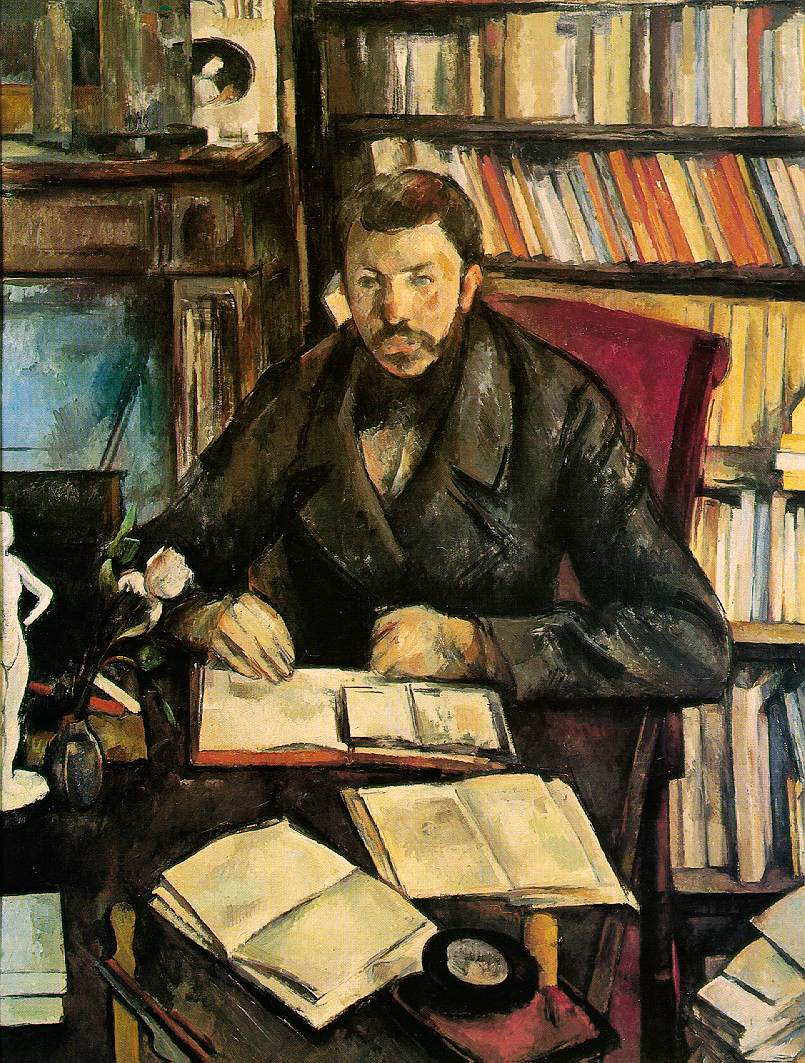

Alice worked with Paul Cezanne's Gustave Geffroy (1895-96) in both her art history and studio classes.

Alice was fortunate to see her painting (on the right wall) in a special Cezanne portraiture exhibition.

Give us some insight into your assigned artwork from the Orsay Musuem. After seeing the work in person in Paris (and any other related art from the same artist or art movement associated with the assigned work), what struck you most about it and/or how did the artwork’s form, content, and context shift for you when seeing it.

The first thing I need to clarify is that I had visited the Orsay Museum twice because my painting was not available the first time I visited it and I had to return to the museum a week later. I will however not complain about having to stand in line all over again because not only do I feel extremely luck that was my painting—Cezanne’s Gustave Geffroy (1895-96)—was available to be viewed, it was part of a special exhibition called Portraits by Cezanne (June 13-September 24, 2017). The exhibition united all the major portraitures painted by Cezanne with Gustave Geffroy being one of the largest ones he ever did. It was the most opportune way to study the specificity of the work while contextualizing it within a broader context of Cezanne’s figurative output.

Gustave Geffroy was an art critic who had written in support of Cezanne. The artist, in turn, has offered his portrait and despite two months of work, left the painting unfinished. In the portrait, Geffroy sits at a desk with textless books open in front of him. The overly large bookcase and furnace behind him appears compressed against his back, conjuring a sense of claustrophobia. There is a distortion of perspective: the desk and chair rotates to the left; the sitter appears frontally; books appear through an aerial view. In the digital reproduction of the painting, the colors appear deceptively mute. In person, I was taken aback by the prominent use of warm colors, and in particular, of the color red. The edges of his books were blood red; there were red pencils, red ink pads, red markers. The seat under him was red; the back of his chair, deep magenta. The rows of books on the shelf adjacent to his head bore varying degree of orange, creating a sense of warmth that contrasted sharply with the coolness of the mauvish-blue fireplace. In comparison to Cezanne’s other portraitures, Gustave Geffroy harbored the most bountiful collection of objects and colors.

None of the formal dynamicism translated into iconography of the sitter’s expression. Like most of the portraitures by Cezanne, Gustave averts his gaze. While Geffroy appears pensive, it can also be argued that he stares into oblivion. I had expected the painting to be more soulful in person than in reproduction and was disappointed to find it to be equally lifeless as the reproduction. He did not bear the express of boredom or apathy; he was simply expressionless. It was as if his face was frozen, that it was still in the stage of becoming. If I had not seen the other portraitures by Cezanne, I would have assumed that this was simply the offshoot of an unfinished painting, that true to primary sources, he had abandoned the painting after two months of work, leaving the face and the hand for particularly premature.

Studying Gustave Geffroy in the context of his figurative paintings seems to suggest a consistent degree of lifelessness in his portraiture. The exhibition, for example, ends with the last self-portrait he did were the expression was equally frozen. To give credit when credit is due, the audio guide for the self-portrait made the observation that the eyes of the figure were painted with indistinguishable iris and pupil. Looking back at Gustave Geffroy, I realized that indeed the eyes are painted in an oddly life-negating manner. The sclera appears dark grey; it darkens into the iris and blends into the void of the pupil. The lack of clarity subverts the notion of translucence that characterizes not only the anatomy of the eyes but of life itself. The figure, while present, is dead. Gustave Geffroy is not a portraiture, it is a still-life.

How did you approach the creative task of responding to this assigned work in studio? What were your challenges as an artist to be in dialogue with the artwork and artist? Would you do anything differently now that you have seen the work in person?

Inspired by both Cezanne’s Gustave Geffroy and Walter Benjamin’s call to study the “refuse of history,” I sought to replicate the physical environment of the painting based on how it was normally hung at the Orsay Museum. The frame and wall were recreated in a miniaturize version with a hamster wheel inserted into the assemblage as a nod to Duchamp and his exploration of institution critique through ready-mades. Seeing the painting’s renewed location in the Portraits by Cezanne exhibition underscored how strategic placement contributes to narrative for me.

In its normal placement, Gustav Geffroy flanks the doorway of an Impressionism room with another large-scale portraiture by Cezanne entitled La Femme à la cafetière (1895). In the catalogue to the exhibition, the paintings were discussed in conjunction, although a clear bias was given to the art critic than the woman who was to become his wife. Seeing La Femme occupying a wall island in the central axis of the second-to-last room was therefore very exciting for me. I expected to see my painting on the opposite of it, thereby also occupying a prominent, albeit floating, presence in the room. To much of my disappointment, it was a small, unfinished oil study hanging on the other side—that of my colleague Lucas Paul’s Le Joueur de cartes (étude) (1890-1892). My painting, which by all expectation was a foil to La Femme, hung unremarkably on the wall in the room along with other portraiture. Upon closer inspection, however, I noticed that the walls were painted with alternating regions of yellow and grey. The colors were demarcating sections of the wall, creating a visual categorization among the works. Gustave Geffroy occupied a region of grey among two sections of yellow; it shared the region with Cezanne’s portraiture of his dealer Ambroise Vollard. One cannot hear a more blatant call for a comparison than standing in front of two paintings united by the same wall color in a room with alternating with visual sectionality.

To venture some guesses, I would argue that several connections can be drawn between Geffroy and Vollard. Both were supporters of Cezanne’s works where critical acclaims and financial success shared a symbiotic relationship. Both portraits are unfinished, with the hands and the faces particularly inchoate. And while Cezanne’s relationship with Geffroy eventually soured, he remained faithful to his dealer, even writing to him to express his most critical opinion of Geffroy. The pairing of the two paintings creates a visual dichotomy that instigates a particular construction of biography. Consistent with the idea of institutional critique that I explored in my artwork, the structure of the exhibition—something as benign as wall color—contributes to the meaning of the works. The derivation of art historical knowledge is not organic to the work but forged through myriad of micro and macro-contextualization in which the format of display plays a critical role.

Today’s activity was located at the Orsay Museum. What were your impressions? What will you take away of the experiences of this day? What are the most memorable moments for you?

Since my two visits at the Orsay Museum were separated by a week’s time during which I recovered from my jetlag, my first and second impression of the museum was very different. In both visits, I had gone in expecting to experience the monumentality of the works, to contextualize the physicality of the paintings I have studied. Seeing Gustave Courbet’s Burial at Ornan (1849-50) during my first visit was an immersive experience. I did not expect it to be nearly as large. The constant scurrying towards and away from the painting turned the work into a portal through which I played tug of war with the artist. The movement exacerbated my jetlag-induced vertigo, inadvertently affording the composition a hallucinatory dynamism.

During my second visit to the museum everything was much more stable. I did not feel overwhelmed by the sculpture-filled central aisle which, during my first visit, had felt clustered like a craft fair. I appreciated the luminosity of the glass rooftop; the remnant signs of the former train station also was a poetic reminder of human ingenuity in both its construction and its reappropriation. I loved the large clocks that adorned the place. They add an interesting temporal element as I traversed centuries of human history in a matter of hours. Drawing a continuity between the past and the present through emphasizing the liquidity of time, the clocks reverberate with a call to action: “You’ve understood where we come from now, where will we be going now?”

After the Orsay, we stopped by a historic art supply store called Sennelier. If Hogwarts ever start an art course, this place could have been easily incorporated into the set with no alternation needed. It was packed to the ceiling with supplies; any niche that can be packed with goods were packed with goods. Everywhere you turned a pocket of richness awaited. There were things that you had been looking for (I found my fountain pen there); and then there were things that you felt compelled to buy simply because it held the promise of infusing your life with some of the artistic vibe in that space. The store was seeped in creativity in the most life-affirming way. Even the most unartistically-inclined souls would step out of there feeling like they have come out of a fairytale.