Scanning through artworks in the MoMA’s collection under the search term “Christmas” for this post, I was immediately drawn to one photograph by Arthur Leipzig that features little kids looking through a toy store window. I was drawn in the way that French literary theorist Roland Barthes talks about when describing the essential element of a successful photograph. The image had a punctum. As Barthes explains, “The punctum of a photograph is that accident which pricks me (but also bruises me, is poignant to me)” and it is an element that you cannot stop looking at, an almost indescribable alignment of signs that makes you keep looking, and looking, and looking. For me, this photograph perfectly encapsulates the conflicting emotions of coming to the end of this annus horribilis and looking ahead, with trepidation, to 2021.

My short read of this image? The little girl wiping away a tear in the central vertical axis of the photograph is all of us. She is isolated and almost invisible to those around her, carrying an emotional intensity that is devastating to confront, but framed in such a way as to demand all of our attention. More than just sad, this child looks exhausted, and the reflection of the house, appearing to superimpose on her body, reminds us of where we have spent so much of our time this year. To her left, an older girl stares with her mouth open. She has a look of shock, maybe a bit of surprise. It is not clear. The half-eaten apple in her hand tells us she has been well distracted from what she had been doing, and that sense of being derailed and disoriented from routine is another feeling we have lived with all year. And finally, the young boy in the right register of the photograph makes direct eye contact with us. He is holding up a hand in a half wave, a sign of greeting, hope, and yes, connection. Yet, he too, appears distant, especially as we see him through glass, the material that represents the separation we have all literally and figuratively been living with since the pandemic began. But it is this same little boy who balances and grounds the picture, letting us know that what we are looking at is not necessarily dangerous, bad, or to be feared. There is hope here, however small.

The person who captured this image, Arthur Leipzig, was a Brooklyn born photographer and photojournalist who took this picture during WWII in New York City. Having studied with famed modernist photographers Paul Strand and later mentored by Edward Steichen, Leipzig worked in a tradition of documenting the lives and struggles of people, subverting the notion of art photography as only aesthetically appealing if representing “beauty.” At the time this image was taken, in 1944, Leipzig was a young man in his mid-twenties two years into his photography career (he was born, ironically enough, the year of the Spanish Flu in 1918). Decades later in his 70s, Leipzig would reflect on his photo practice in a memoir Growing Up in New York revealing the many risks to his career and misunderstandings that came with taking these kinds of photographs. “No photograph,” he wrote “no matter how good it is, is worth hurting people.” Still, Leipzig appeared to understand that the power of a well-taken photograph was all about its unmistakable punctum, and the ability of a photographer to capture something of our unrehearsed selves.

Wishing all of you the very best of this holiday season. Stay safe, be well, and take a moment this week to celebrate the art and artists in your life that helped make 2020 a bit more bearable. Enjoy the links!

From Graffiti to the Gallery, Futura Talks About Art (PODCAST)

Could Social Media Innovators Like Elsa Majimbo Help Gen Z Rewrite Cultural Norms

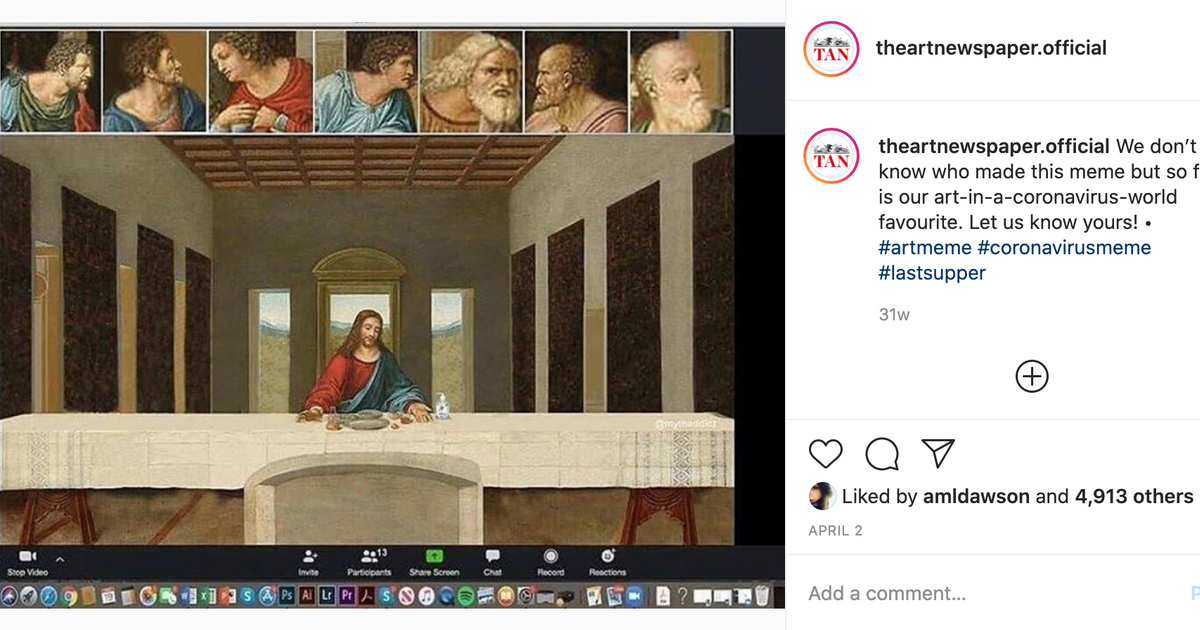

The top five Instagram posts that capture the art world in 2020

Steve McQueen’s Education presents a moving history lesson on racial bias

Engineer, Agitator, Constructor: The Artist Reinvented | MoMA (VIDEO)