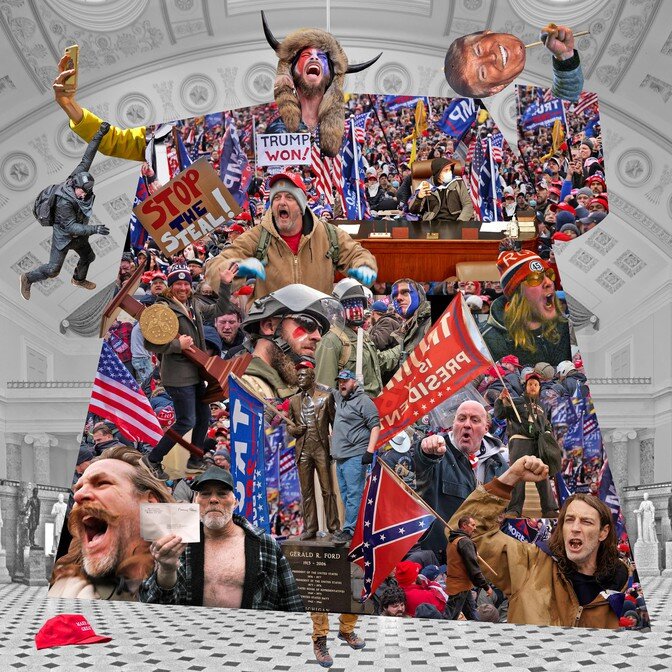

As I write this post, the visual evidence of the Trump-fueled insurrection at the US Capitol on January 6th continues to pour in and shape the conversation around both the seriousness and severity of the event, but also about how to “read” what actually happened. As with many of you, my first real apprehension of the day’s events happened once I turned on my television and opened my social media feeds in order to take in the motion pictures, stream of photographs, and media accounts that were often happening live and in real-time.

We all of course take for granted that these images will exist and be forever available to us. More importantly, we are conditioned to trust and take filmed and photographed documents at face value, and as factual evidence. Going back in the history of photography, I often lecture about the 1871 Paris Commune—a revolutionary government that ruled after a four month siege and violent insurrection—and the important role of photographers in communicating the scale of death and destruction. As a relatively new and still-evolving medium, the photograph had a power to undermine and displace textual or artistic representations of that fraught historical moment. The images were also impossible to control, at least at first, and the photographs of real people lying dead in Paris streets were largely shown as unromanticized images of raw carnage. The photographs were also quickly distributed around the world, taking on new meanings and political and symbolic associations at times far removed from the original events. But in later years, many of the photographs would disappear and be banned from sale and forbidden from public view or archiving in France.

Architecture and art critic Michael Kimmelman tweeting on the Trump Insurrection this past week.

As someone who studies failed revolutions and insurrections, especially within the context of art movements, I can’t help wondering how our current moment parallels something of what was seem with the advent of politized photographs during the late 19th century. At once a medium associated with unquestionable truth, but also one open to wide distribution, manipulation, and erasure, the photograph of 1871 has many similarities to social media platforms today. There will no doubt be a much needed reckoning about the role of openly accessed social media and the fractured news environment when this episode of history is finally written. Architecture and art critic Michael Kimmelman was quick to respond and point out on Twitter how the preservation of the markers of the January 6th event—even at the level of damaged and defaced monuments and statues—needs to be maintained in order to preserve the evidence of the moment, while countering the impulse to “move on” and forget the reality of what took place. How will this avalanche of evidence— from social media posts, images, videos, to the actual physical evidence of mass violence— be collected, documented, and archived?

A number of the articles in my round up this week speak directly to this idea. Moreover, it will be important to pay attention to how artists, art critics, and art historians respond to and represent the Trump-fuelled insurrection in the weeks, months, and years to come.

A few more things before the round up:

A book for our moment, Hal Foster’s essays speak to “a world where truth is cast in doubt and shame” and asks what artists, art critics, and art historians are left to do.

During these precarious Trump years, art historian, theorist, and critic Hal Foster has spent a great deal of time and energy writing about how to demystify the current global political climate from within the framework of the art world. His recently published book of essays What Comes After Farce? Art Criticism At A Time of Debacle (Verso, 2020) was a book that I finally had a chance to read more thoroughly over the Christmas break as I worked on some new writing projects, and it is a book that I recommend widely to anyone, and especially artists, who wants a sense of what the future of a post-Trumpian era art world might look like.

Speaking of insurrection and civil unrest, the 2019 BBC adaptation of Les Miserables is debuting in Canada on the CBC tonight. Starring Dominic West (who I just finished watching through a 2020 binge of five seasons of The Wire), Lily Collins (Emily In Paris—and yes, I watched that too), and the amazing Olivia Colman (The Crown and Fleabag), the eight-part mini series could not have debuted at a more perfect moment, and promises to continue conversations around the history of revolutions, formations of democracy, and class warfare. DVR is set.