Minimalism has been on my mind a lot the past several weeks. It is normally this time in the spring semester when I start introducing the concepts surrounding one of the most enigmatic and difficult to apprehend post-WWII art movements in my Contemporary Art course. With a focus on form and materials, and a rejection of biography and metaphor, Minimalist art was a complete abdication of the traditions associated with the “genius artist” and the privileged art object. Instead, artists associated with the Minimalist art movement focused on challenging audiences to confront the experience of physicality, scale, materials, and light in a given space.

Right now and for the past few months, it seems that all of us are being forced into something of this position during the darkest period of the pandemic. With increasing limits on the spaces we can inhabit, and being limited to who we can interact with, we are collectively being made to look more closely to our own immediate environments. And along with looking, we are also being made far more aware of how we feel and embody the spaces we are living in.

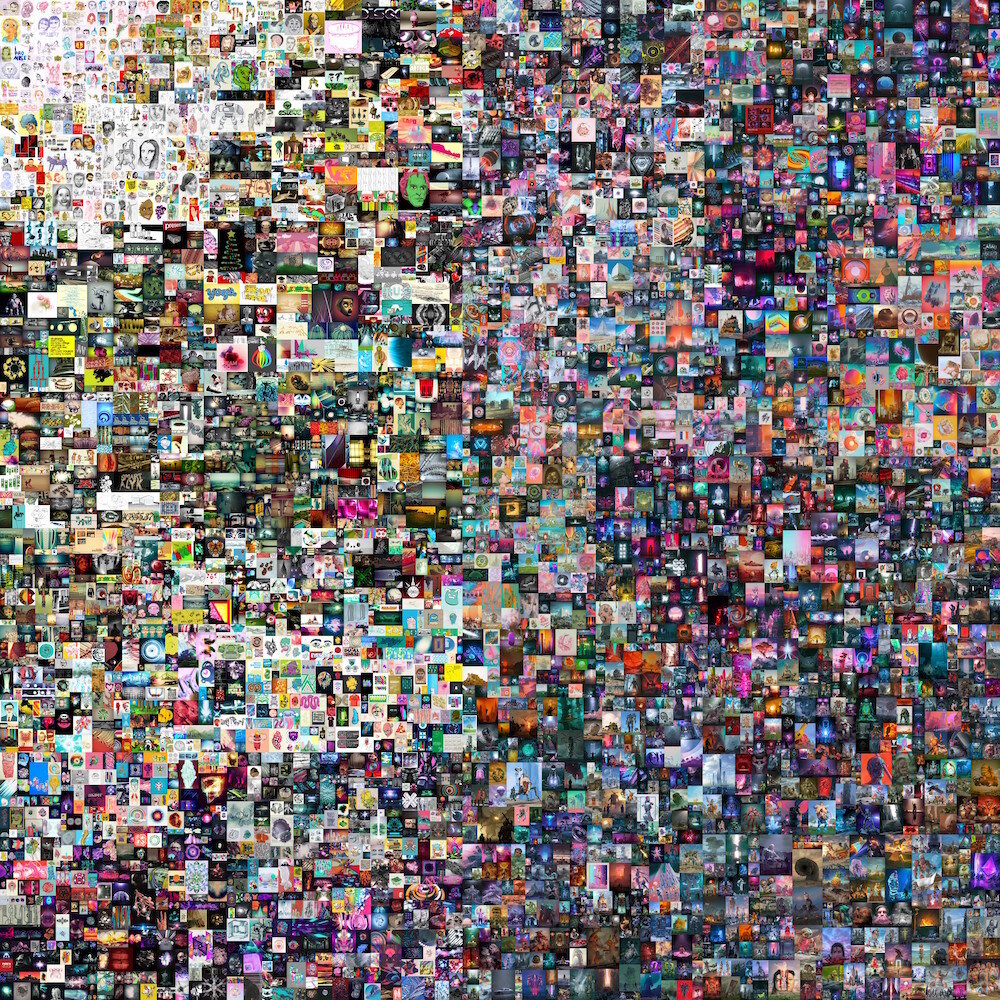

In 2012, I visited the MUMOK Museum in Vienna, Austria to see a Dan Flavin retrospective. Room after room, and floor after floor, was filled with nothing else but Flavin’s iconic minimalist light installations, creating one of the most memorable experiences I have ever had in a vast gallery space. Photograph: D. Barenscott

Earlier this year, art critic Kyle Chayka, author of The Longing For Less: Living With Minimalism (2020) wrote an intriguing feature article for the New York Times titled “How Nothingness Became Everything We Wanted.” Therein he presents a compelling argument about how a pre-pandemic shared aesthetics of nothingness resulted in a kind of “jettisoning of possessions.” Whether it be through the popularity of lifestyle guru Marie Kondo who promoted ruthlessly reducing and then carefully arranging objects in lived spaces, or via stripped down minimalist fashion brands like Everlane, or the growth of the sensory deprivation industry and the popularity of meditation apps on our phones, there was a traceable precursor to a much more profound moment shaping our Covid and possible post-Covid world. Chayka writes:

“This obsession with absence, the intentional erasure of self and surroundings, is the apotheosis of what I’ve come to think of as a culture of negation: a body of cultural output, from material goods to entertainment franchises to lifestyle fads, that evinces a desire to reject the overstimulation that defines contemporary existence. This retreat, which took hold in the decade before the pandemic, betrays a grim undercurrent: a deepening failure of optimism in the possibilities of our future, a disillusionment that Covid-19 and its economic crisis have only intensified. It’s as if we want to get rid of everything in advance, including our expectations, so that we won’t have anything left to lose.”

While indeed grim and pessimistic in tone, what I take from Chayka’s analysis of our own 2020-2021 minimalist moment is also something productive and affirming. As with the Minimalist art movement of the 1960-70s that sought to radically redirect the energies and purpose of art making to more inclusive and democratic ends—directing audiences to confront the absence of distraction and “things” – there is an urgency and creative energy in our current circumstances. We are living with a heightened and acute sense of our space and place in the world, and this has the strong potential to recast the role and place of nothingness in our post-pandemic lives. Minimalists rejoice (maybe).

A few more things before the round up:

If all of this talk of Minimalism has you intrigued, I highly recommend the television show I Love Dick (on Amazon Video— see trailer below) set in the Minimalist Mecca known as Marfa, Texas. The show is based around an academic community where the main characters, a filmmaker and her husband who has taken up a research fellowship at the Marfa Institute, interact with a renowned scholar (played by Kevin Bacon) who also happens to be a minimalist artist.

And speaking of space, there has been much discussion in the academic community and on academic Twitter about the very real problems with remote learning. If teaching real bodies in real space is something you want to ponder further, I recommend this Chronicle of Higher Education article, “What We’ve Lost In A Year of Virtual Teaching.”