I take great comfort in being a historian entering the third year of the pandemic. There is something very grounding in looking to the past and seeing that what we are living is not necessarily unprecedented nor without parallels and knowable outcomes. Back in 2020 when news of the first wave was upon us, I devoured Laura Spinney’s Pale Rider: The Spanish Flu of 1918 and How It Changed the World (ironically enough written in 2018 before Covid was on the world’s radar) to remind myself that this often neglected moment in twentieth century history—the one that also has shaped my own research interests— would shepherd in one of the most significant decades of artistic, avant-garde, and cultural developments the world had ever seen.

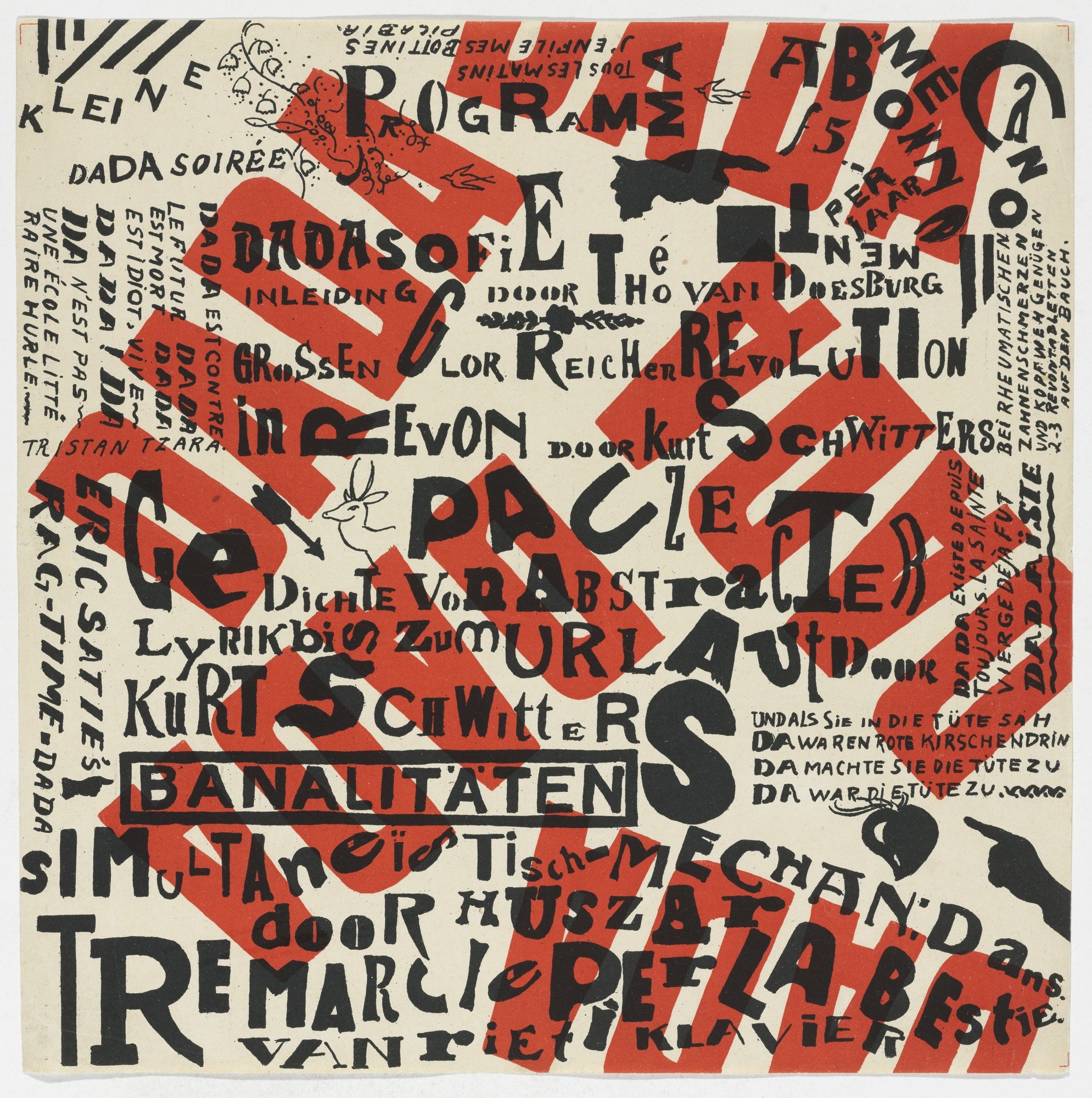

Over the past two years, teaching my film and art history students about the significance of Germany’s Weimar Republic (1918-1933), and the rise of art movements such as Dada, Surrealism, and Expressionism, has taken on an especially relevant meaning. Take for example my featured artwork—Theo van Doesburg and Kurt Schwitters’ Kleine Dada Soirée—a poster created one hundred years ago in 1922 to introduce an art movement that, as the Tate Modern aptly describes, reveled “in the destruction of all traditional values in art and to create a new art in its place.”

Raoul Hausmann, The Art Critic (1919–20), a perfect example of the Dada ethos to question and undermine traditional conceptions of art, art institutions, and the authorities policing art's boundaries. Via Tate Modern Collection.

Asking young creatives to think about what it means for an entire generation of artists to look at the chaos in their world and go on to reshape and reimagine all manner of art, cultural, and ingrained social and political traditions is profoundly affirming. Change, at all levels, is what we are looking at in the decade to come post-Covid.

One of the other things I have been inviting students in my classes to do over this past year is to explore city (local and international) and art museum archives from around the world and examine the photo-documentation and art works of the period immediately before, during, and after the 1918 pandemic to look for traces and evidence of these transformations. I have heard back through many reflective assignments from these same students about the hope, new perspective, and sense of living through a historically significant period they gain through this kind of exercise. Seeing the visual and creative evidence of earlier cultures surviving and living through a global pandemic is both humbling and encouraging. Recognizing the past mirrored in our present provides reassurance and a sense of resolve.

So, as we kick off a new year and a new academic semester in a world filled with fear and doubt, I want to find more moments of grace, as a historian and as an educator, to focus on where the possibilities lie.

A Few More Things Before the Round-Up…

This past semester was one of the most demanding and difficult of my career for a whole host of personal and professional reasons. On many levels, I was left feeling quite exhausted and at my limits, but I also know I was not alone. Listening to The Professor Is In’s last podcast of the year “Your Breaking Point” was revelatory and provided a moment of grounding and recalibration to set out for a new year. Educators and students alike will find lots of valuable ideas in this resource.

On a much lighter note, I binge watched all four seasons of Yellowstone over the holidays (it’s like HBO’s Succession, but out in Montana), and I cannot recommend it highly enough for all of the relevant themes around capital expansion, environmentalism, income inequality, and fight over Indigenous rights. I am now watching the prequel to the series, 1883, and it is equally compelling.