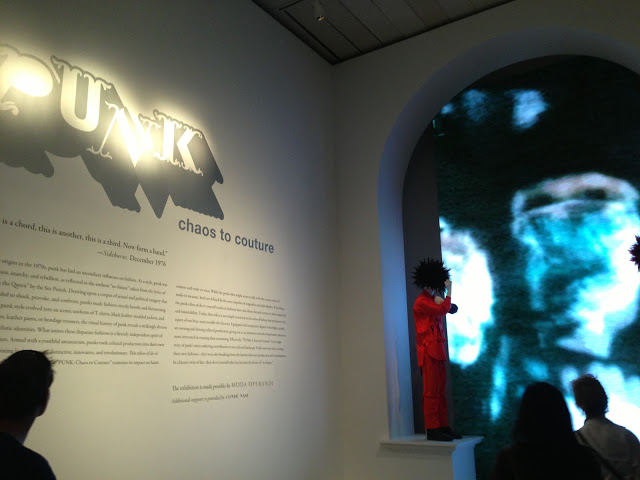

Punk culture and the avant-garde have much in common—they are both difficult to define and everyone has their own idea of what each is. Perhaps that it is why the world of fashion loves the designation of punk or avant-garde couture. With the air of the risqué and subcultural associations, the notion of “punk” comes with the promise of something new, something spectacular, the next big thing everyone will be talking about. A few weeks ago while I was on a research trip to New York, I visited the Metropolitan Museum’s much hyped Punk: Chaos to Couture Exhibition to see just how an art museum would handle the curation of a show dedicated to punk aesthetics. In many ways, it seems like the perfect marriage—an art institution displaying the most out-of-the-box examples of fashion, merging creative experimentation and “fashion as art” discourses. At the same time, removing the clothing from the runway off the model’s bodies and displaying them as ‘art objects’ in a museum forces a new kind of engagement for the public.

The debates around punk generated by the Met Ball opening were decidedly superficial. Image: Fashionista.com

I have been thinking a great deal about the intersection of fashion and art over the past year (in fact, I blogged about the Alexander McQueen show at the Met two years ago), and I was especially intrigued to see this exhibit running concurrently with the Orsay Impressionism and Fashion Exhibition, which happened to be on display at the Met at the same time on the same floor. Only a few short weeks earlier, the annual Met Gala had opened the Punk Exhibition and caused some interesting discussion about who had managed to nail the punk aesthetic in their red carpet looks. A protest had even formed around the opening in an attempt to draw attention to the subversive roots of the punk movement, with the organizer of “Punk OUT”, Geraldine Visco, questioning both the exhibit and the decidedly “bourgeois” and superficial celebration of punk aesthetics surrounding its opening:

“Our band of “punks” was composed of a ragtag dozen artists and performers from 21 to 58 years of age who’ve been inspired by or involved with punk music, fashion, and the lifestyle. There are no real punks and never have been, since once you call yourself a “punk,” you have become a yuppie in a T-shirt and black leather. Nonetheless, the punk lifestyle and art during the 1970s and 1980s was real and it is still an important influence in art, music, politics, and yes, fashion. We weren’t angry about the show, just disappointed that the Metropolitan Museum has become more and more corporate and less interested in documenting punk and what it has influenced in a serious, well-rounded way — recognizing that the punk aesthetic has always fought against commercialism and corporate culture.”

No doubt the protesters were tapping into one of the persistent tensions within outsider and avant-garde cultures—the specter of assimilation and appropriation by the masses. It was the same issue that plagued the Impressionists when the shock of their new art wore off and people began to appreciate modern painting as something worthy of praise and, yes, purchase. Strolling through the Impressionist Fashion exhibition, very little of the radicality associated with early Impressionism remained. One would have to study the paintings very closely and with a learned eye to pick out the more scandalous elements of paintings that actually poked fun and made commentary on middle class pretensions and aspirations (it was fantastic, for example, to see Courbet’s Young Ladies on the Banks of the Seine (1857) and Manet’s Woman Reading (1879) up close).

Walking into the Punk Exhibition, I was struck at first by the installation of a recreated punk club bathroom—right down to the urine encrusted and cigarette littered floor. Now this could be interesting I thought. Welcoming audiences into the dark and subterranean world of punk via the nightclub was intriguing—a space of high contrast to the pristine and controlled world of the fashion runway. But once past the entry, the exhibition itself proved quite conventional. Faceless mannequins dressed in couture clothes were presented in groups, in rows, and yes on runways in a very un-punk like way. Even the fake graffiti on the walls seemed too well placed and contrived. And while the punk music blaring from the overhead speakers and strobe lights added some unique atmosphere, the show itself was not especially groundbreaking nor did it require much of the audience in terms of critical reflection. In fact, just as many people were impressed with the “labels” attached to the punk objects (oh look! a Chanel, a Givenchy, a Vivienne Westwood!) as they were with the Impressionist show (oh look! a Monet, a Renoir, a Cassatt!). See the Met's Gallery Views and commentary in the YouTube clip below for more interior views of the exhibition.

Walking down 5th Avenue later that day, I was struck by the number of high-end retailers who had decorated their windows with a punk theme—I chuckled wondering what store clerks in Bergdorf’s would actually do if the punk rocker they had placed in their window came to life and strolled into their establishment.

And while all things punk related seem to be for sale in New York and trending culturally in popular culture (didn’t Daft Punk just drop a new album?), when I arrived home, I was intrigued to read how quietly the arrival of real punk rockers Pussy Riot (to New York City no less) was covered in the mainstream press. As the New York Times reported, they had come to NYC to promote an upcoming HBO documentary concerning their activist cause in Russia:

“Without fanfare, two members of the collective slipped into New York in the last week, to help promote the film and meet, undercover, with supporters. It is their first time in America. At the theater, they munched popcorn as a slew of well-heeled New Yorkers and boldface names — Salman Rushdie, Patti Smith — sauntered by. A few guests wore “Free Pussy Riot” T-shirts, oblivious to the still-at-large members in their midst. There was a party afterward, but for Pussy Riot, this trip was a serious effort to expand their reach without compromising their credibility as artistic revolutionaries.”

And so, resisting the lure to compromise artistic principles and the DIY ethos attached to punk culture continues on, however quietly. Does this mean that punk culture is still alive and well? Perhaps. Or maybe it is blurred into the cultural landscape in new and unpredictable ways. I must say that the photograph used by the New York Times, for example, to cover the Pussy Riot visit has vague similarities to an editorial spread from a fashion magazine or maybe an Urban Outfitter ad—but I digress. In the end, the conversation around punk culture and its intersection with fashion remains very intriguing despite what the Met show attempted to reveal… or hide.

NYT's cover photo for their story on punk rock group Pussy Riot-- curious who styled this shoot. Image: New York Times

Further Reading:

Barrett, Dawson. "DIY Democaracy: The Direct Action Politics of American Punk Collectives." American Studies vol. 52.2 (2013): 23-42.

Sanders, George. "Punk May Just Be Dead." Critical Sociology vol. 39.2 (2012): 295-301.

Savage, John, William Gibson et al. Punk: An Aesthetic. Rizzoli: 2012.