How do I say this in the nicest way possible? No, I will not be going to that immersive Van Gogh exhibition. I have tried to avoid talking about this particular show since it hit my city, and remain tactful when it is brought up in conversation. I try really hard to change the subject before the inevitable question arises—“so, when are you going? Isn’t it so exciting?”—and avoid appearing like a total art snob or intellectual elitist when I have to answer as diplomatically as possible that no, in fact I will be passing on that show.

Van Gogh is one of those artists around whom art historians have very charged emotions and experiences. His persona looms large, especially for those of us who specialize in modern and contemporary art, and we spend a great deal of time challenging a lot of the stereotypes and cult of personality that accumulate in the canon of art history around “genius artists” like Van Gogh. In a nutshell, the problem with Van Gogh is one of both the commodification of his art and the distancing of the circulating meaning of his works from their original context. Not unlike the Impressionists and artists like Monet and Renoir who are now largely identified through the confectionary visual vocabulary of flowers, ballet dancers, and many art gift store decorations fit for little girls and grandmothers, the Van Gogh “brand” is closely linked with the spectacle of consumer culture and the narrative of the suffering artist.

A promotional image of the immersive Van Gogh show that has been making its way around the world in the past year. Image source: Toronto Star

The persistent focus on Van Gogh’s psycho-biography and how this creates the intention and meaning around his art presents art historians with one of the toughest fallacies to overcome in the teaching of modern art. The irony is that the modern art movement, of which Van Gogh was both a leader and catalyst, was part of an unfolding revolution (social and politically charged) by generations of avant-garde artists in the rendering of form and content in painting. Van Gogh’s paintings were radical acts in and of themselves and not the stuff of décor, entertainment, or meditations on his mental health.

I recently read a review by Guardian art critic Andrew Frost, aptly titled “Van Gogh Alive—resurrecting the dead in a glossy, impersonal blockbuster,” that comes close to capturing my thoughts on what is so wrong with this show. “: “…death has taken Van Gogh’s art and his biography and made it the stuff of entertainment, and no matter how reverent or meaningful its makers might think it is, they’ve merely created a feed point from which his art endlessly circulates in the world system of social media, images disconnected from their maker, just another visual distraction alongside good doggos, funny cats, and Trump speeches.”

The technologically intensive and immersive Van Gogh experience does nothing to recognize or situate the artist in his historical moment. Worse, the very means of representation chosen by the show’s organizers—cinematic, large-scale, and theatrical—has little to nothing to do with the quiet canvases Van Gogh created in his relatively short career. How and why his legacy (long after his death) ended up in the state we find it today is the stuff of many of my lectures, and suffice it to say here that much of it has to do with the agenda of influential art collectors and institutions, reinforced by art historical narratives, that many in my field dutifully work to expose, unpack, question, and over-turn.

So no, I won’t be supporting this show or the manufactured hype of the Van Gogh brand. It all goes against too much of what I do as an art historian. But I also won’t judge too harshly if you go. I enjoy pop culture too and a decent spectacle here and there. But if you were to ask me where your art-going dollars might be better spent, I would urge those locally to attend the Vancouver Art Gallery’s upcoming exhibition “Vancouver Special: Disorientations and Echo’’ It is a show that surveys the current state of contemporary art in the city, along with featuring emerging artists, who in the spirit of the Van Gogh many of us prefer to uphold, are looking for their own visual vocabulary and point of radical intervention in the art world. As the VAG promises, “Encompassing a variety of media, scale and modes of presentation, the artworks that comprise the exhibition address themes that include cultural resilience, the articulation of suppressed histories, the performance of identity and embodied knowledge.” Money much better spent in my humble opinion.

How Red Dresses Became a Symbol for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women

Unplanned Parenthood: Photography and Family Life in a Pandemic

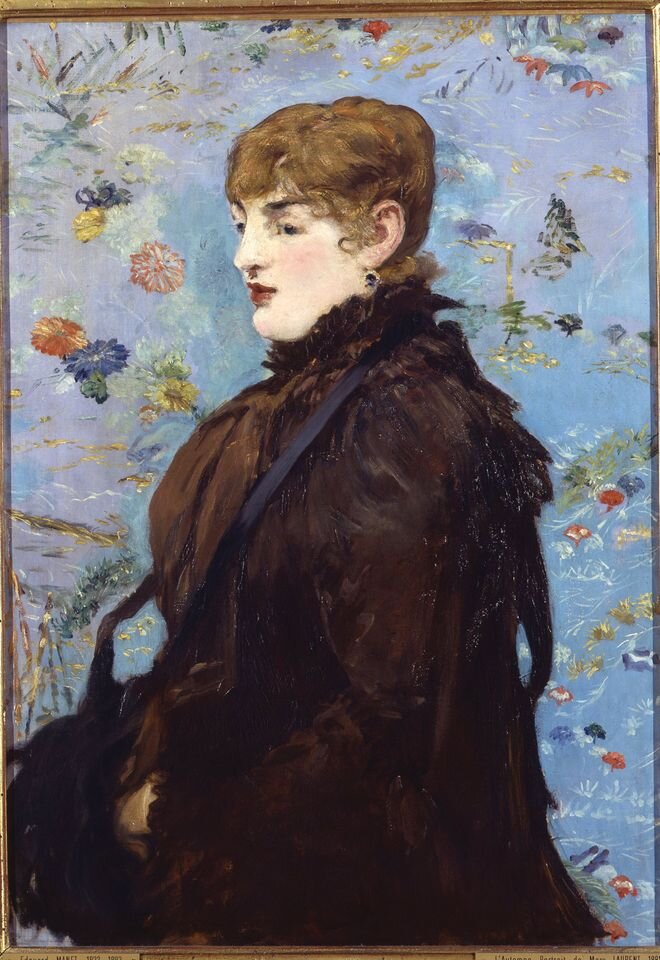

Édouard Manet and modern beauty: prettier, more frivolous and gallant

Tracey Emin on her cancer self-portraits: ‘This is mine. I own it’

Crowds flock to revamped Uffizi Galleries—but can't post pictures on social media