There’s a great line in the “Versailles” episode of Halston, the new Netflix biopic miniseries based on the fashion designer’s life, that sums up the existential question that many artists end up pondering at some point in their career. Halston turns to a trusted friend and asks, “Which is it do you think, am I a businessman or an artist?” By this point in the story, we have learned about the fashion designer’s early years struggling as an unknown window dresser and milliner, but then also of his big break in 1961 when Halston achieved overnight fame by designing the signature pillbox hat worn by Jacqueline Kennedy to her husband’s presidential inauguration. Fast forward to the early 1970’s and we see a designer evolving into one of the most powerful fashion brands in the United States. From there (spoiler alert), the story takes a dark turn.

The moral of the story is already foreshadowed in that same early episode. For when Halston ponders that question, his friend, prominent fashion publicist Eleanor Lambert, perhaps most famous for creating New York Fashion Week and founding the Met Gala, replies, “you have to choose?” and Halston answers without hesitation, “yes, I probably do.” And back in the mid-1970-80’s, well before the advent of lifestyle marketing, the Internet, social media, influencers, and the final collapse of the historical avant-garde, there yet existed a fine and perceptible line between “high art” and the pedestrian culture of mass-produced goods.

In this sense, Halston’s story is a fascinating look at the world of art and fashion in the years immediately preceding what art historian’s term the “postmodern” turn in art and visual culture. These were the same years when art world “superstars” Andy Warhol and Jean-Michel Basquiat, were largely ignored, overlooked, and seen as vulgar and déclassé by art world elites. Serious artists did not co-mingle with celebrities, nor did they pursue commercial interests (at least not overtly). Legitimate artists did not look to the “everyday” or the streets for their inspiration. So, does that mean today things have ideally changed? Maybe, but only for the lucky few.

Halston and Warhol were life long-friends and both came to prominence following early careers in advertising. In the early 1980’s as Halston’s brand was becoming more and more diluted into the mainstream, the designer hired Warhol to create four double-page advertisements for his fashion line in an attempt to build cultural capital for his brand. Ironically, Warhol was already by that time beginning to diminish in the eyes of the art world elite who declared him merely a “business artist.”

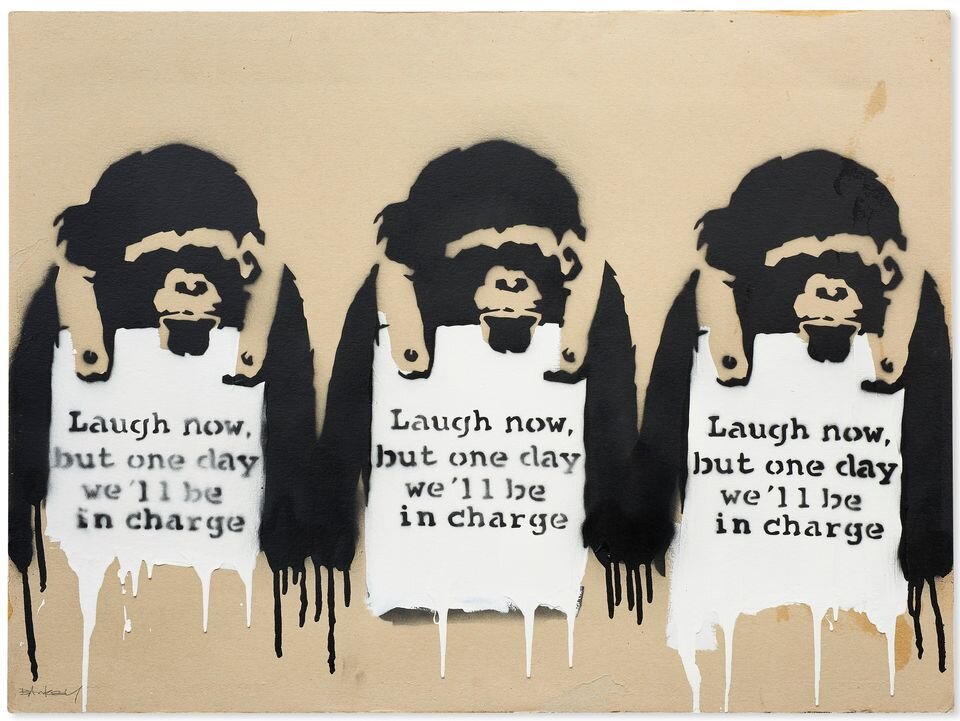

This is still one of the hardest concepts for many of my students to understand—the idea that despite the postmodern turn, which includes the co-mingling of “high” and “low” culture, interdisciplinary experimentation, and the acceptance and even celebration of differences in identity, gender, class, and the like, there is still a gate-keeping function within the art world that declares who is “in” and who is “out” at any given time. Indeed, popular contemporary artists of today, the ones whose names are most often recognized by the masses (i.e. Banksy, Jeff Koons, Takashi Murakami, KAWS, etc..) are also still largely ignored or dismissed by many art world insiders specifically because of their ties to commercial branding and/or rise through street and graffiti culture. Sound familiar?

The art market only complicates these calculations and helps determine other forms of “value” that appear at times to supersede what is understood as legitimate art by art elites, but the bottom line is that an often-enigmatic cultural capital accrues around those artists and designers who are never directly accused of “selling out” or, worse, becoming business men and women, despite them clearly being a brand. Until this system is more fully interrogated and brought to public scrutiny, artists will find themselves asking the very same question that wracked a talented artist and designer fifty years ago at a key moment in their career. Some things never really change.

A few more things before the round up:

The Halston Netflix series is based on the book Simply Halston, a now out of print book by author Steven Gaines. This got me thinking of all the fantastic fashion biographies and non-fiction accounts out there I have read over the years. If you are new to this genre, I can recommend three off the top of my head: Alicia Drake, The Beautiful Fall (2009); Dana Thomas, Deluxe: How Luxury Lost Its Luster (2007) and Gods and Kings (2015) and; Teri Agins, The End of Fashion (2010).

Another book that has been on my radar related to the topic of North American art and fashion in the formative decades when Halston or Warhol would have been art students is Louis Menand’s The Free World: Art and Thought in the Cold War (2021). I have included a podcast link in my weekly roundup for an interview with the author, but you can find the New York Times review for the book here.